The HFACS Framework

About the HFACS Framework

The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) was developed by behavioral scientists in the Unites States Navy. The development of HFACS was spurred by increasing problems with human performance.

In order to evaluate how performance decrements were affecting aviation accidents, Drs. Wiegmann and Shappell turned to scientifically valid accident investigation frameworks. What they found was the Swiss-cheese model of accident causation developed by Dr. James Reason.

The Swiss-cheese model

The Swiss-cheese model (Figure 1) takes a systems approach to accident investigation. With this approach, human error is viewed as a symptom of a larger problem in the organization, not the cause of the accident. Within an organization, barriers are established to prevent adverse events. To be most effective, multiple levels of barriers should be established. Reason argues that most organizations have established four separate levels of barriers. The four levels of barriers are sequential in nature, meaning that those levels at the top affect the levels below. Within each level, failures can cause holes in safety barriers. These failures can either be active, those occurring immediately prior to an accident and directly impacting events, or latent, those removed temporally from the event and not exhibiting a direct impact But what exactly are these holes in the safety barriers and how can they be systematically identified?

The HFACS Framework

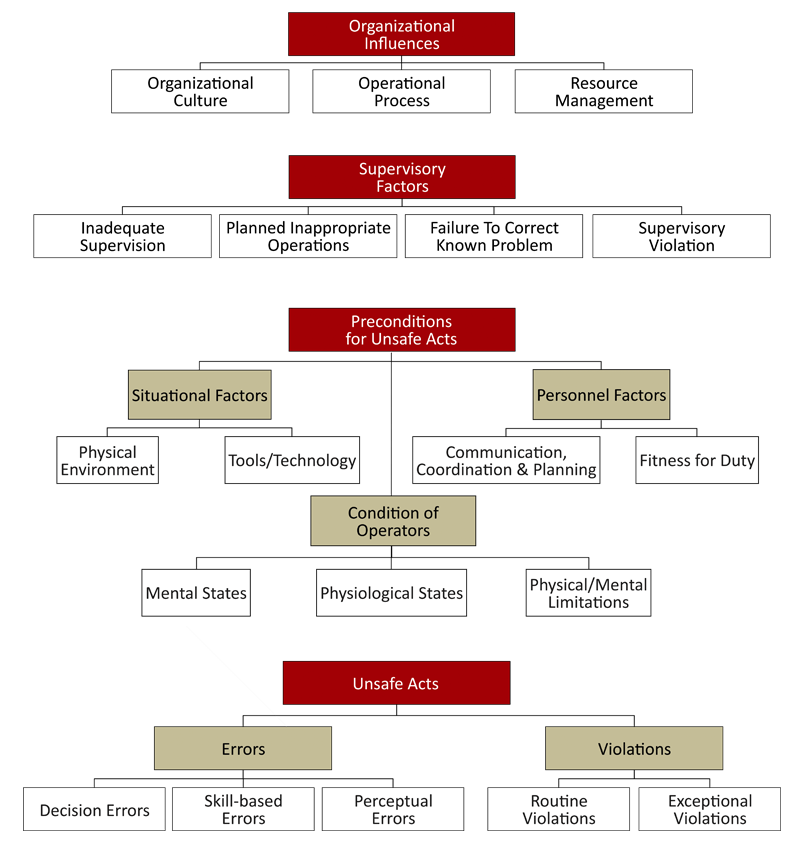

These are the questions that Drs. Wiegmann and Shappell answered with the development of the HFACS framework (Figure 2). HFACS uses the same levels presented by Reason in his model; organizational influences, unsafe supervision, preconditions for unsafe acts and unsafe acts. Within each level of HFACS, causal categories were developed that identify the active and latent failures that occur (see Table 1 for a definition to each causal category). In theory, at least one failure will occur at each level leading to an adverse event. If at any time leading up to the adverse event, one of the failures is corrected, the adverse event will be prevented. Using the HFACS framework as a guide, accident investigators are able to systematically identify active and latent failures within an organization that culminated in an accident. The goal of HFACS is not to attribute blame, rather to understand the underlying causal factors that lead to an accident.

Using HFACS to Identify Trends

But how do you identify these failures before they occur? By reviewing and analyzing historical accident and safety data. The answer may seem simple, but without a structured and scientifically validated framework, it is often difficult to compare one accident to another. For example, how do you compare pilots entering the wrong information into the flight management system to ramp personnel incorrectly loading cargo? By using the HFACS framework, these two events can be compared not only by the psychological origins of the unsafe acts, but also by the latent conditions within the organization that allowed these acts to happen. When events are broken down into the underlying causal factors, it is then that common trends within an organization can be identified.

In identifying common trends, an organization can start to identify where interventions are needed. While traditional approached to intervention development are generally successful at preventing the same or similar accidents from happening again, how do we use our historical data to protect against a variety of accidents? After all, isn’t the goal of accident investigation to reduce the frequency and severity of accidents? By using HFACS, an organization can identify where hazards have arisen historically and start to prevent against these hazards leading to improved human performance and decreased accident and injury rates.

HFACS is Used in a Variety of Industries

While the HFACS framework has seen remarkable success in a variety of industries (e.g. mining, construction, rail and healthcare), the first successful use of the HFACS framework occurred where the framework originated, the US Navy. As stated earlier, the US Navy was experiencing a high percentage of aviation accidents associated with human performance issues. Using the HFACS framework, the Navy was able to identify that nearly one-third of all accidents were associated with routine violations. Once this trend was identified, the Navy was able to implement interventions that not only reduced the percentage of accident associated with violations, but sustained this reduction over time.

By using the HFACS framework for accident investigation, organizations are able to identify the breakdowns within the entire system that allowed an accident to occur. HFACS can also be used proactively by analyzing historical events to identify reoccurring trends in human performance and system deficiencies. Both of these methods will allow organizations to identify weak areas and implement targeted, data-driven interventions that will ultimately reduce accident and injury rates.